A talisman or amulet is a small object intended to bring good luck and/or protection to its owner.

A talisman (from Arabic tilasm, ultimately from Greek telesma or from the Greek word “talein” which means “to initiate into the mysteries.”) consists of any object intended to bring good luck and/or protection to its owner. Potential talismans include: gems or simple stones, statues, coins, drawings, pendants, rings, plants, animals, etc.; even words said in certain occasions – for example: vade retro satana – (Latin, “go back, Satan”), to repel evil or bad luck.

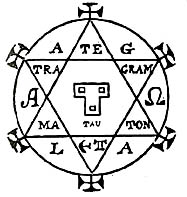

The word talisman also describes a number of consecrated magical objects used in Hermeticism.

Instructions for how to create a talisman can be commonly found in Grimoires. These talismans, sometimes called pentacles, were usually either made to protect the wearer from various influences of disease and other forms of danger or to protect the wearer from demons and to seal a certain demon under the users control.

A common version of the later talisman is known as the Seal of Solomon. This became an extremely important talisman due to the legend that Solomon used demons to create Solomon’s temple and was protected by a seal sent by God (although the earliest accounts describe this seal as a ring: see Testament of Solomon; later innovations were made by various ceremonial magicians and authors of other grimoires where they have described the seal as a ring.)

A common version of the later talisman is known as the Seal of Solomon. This became an extremely important talisman due to the legend that Solomon used demons to create Solomon’s temple and was protected by a seal sent by God (although the earliest accounts describe this seal as a ring: see Testament of Solomon; later innovations were made by various ceremonial magicians and authors of other grimoires where they have described the seal as a ring.)

Talismans vary considerably according to their time and place of origin. Nevertheless, religious objects commonly serve as talismans in different societies, be these the figure of a god or simply some symbol representing the deity (such as the cross for Christians or the “eye of Horus” for the ancient Egyptians). In Thailand one can commonly see people with more than one Buddha hanging from their necks; in Bolivia and some places in Argentina the god Ekeko furnishes a standard talisman, to whom one should offer at least one banknote to obtain fortune and welfare.

Every zodiacal sign has its corresponding gem that acts as an talisman, but these stones vary according to different traditions.

An ancient tradition in China involves capturing a cricket alive and keeping it in an osier box to attract good luck (this tradition extended to the Philippines). Chinese may also spread coins on the floor to attract money; rice also has a reputation as a carrier of good fortune.

Turtles and cactus can cause controversy, for while some people consider them beneficial, others think they delay everything in the house.

Since the Middle Ages in Western culture pentagrams have had a reputation as talismans to attract money, love, etc; and to protect against envy, misfortune, and other disgraces. Other symbols, such as magic squares, angelic signatures and qabalistic signs have been employed to a variety of ends, both benign and malicious.

The Jewish tradition is quite fascinating; examples of Solomon era talismans exist in many museums. Due to proscription of idols, Jewish talismans emphasize text and names- the shape, material or color of an talisman makes no difference.

Rider-talismans such as this one were popular, possibly among Jews and certainly among Christians as all-purpose protective devices. The imagery — a mounted warrior subduing a prostrate enemy — is common enough in many cultures, and its adoption as a symbol in the fight against demons is readily understandable. On this talisman, as on many others, the rider is identified as Solomon, the wise biblical king whom post-biblical traditions turned into an expert in all occult sciences, and especially the subjugation of demons. Thus, Jews and Christians alike invoked Solomon’s name in exorcism rituals, and told stories of the wonderful seal with which he “muzzled” and “sealed” every evil spirit. On this talisman the key, like God’s seal, symbolizes the power to shut the demons in and prevent them from doing any harm.

The Jewish tallis (Yiddish-Hebrew form; plural is talleisim), the prayer shawl with fringed corners and knotted tassels at each corner, is perhaps one of the world’s oldest and most used talismanic objects. Originally intended to distinguish the Jews from pagans, the prayer shawl is considered fascinating because of its name: it is very close to the term “talisman”.

A little-known but well-worn talisman in the Jewish tradition is the kimiyah or “angel text”. This consists of names of angels or Torah passages written on parchment squares by rabbinical scribes. The parchment is then placed in an ornate silver case and worn someplace on the body.

The similarities between Jewish and Buddhist talisman traditions is striking. (see Buddhism below.)

In Afro-Caribbean syncretic religions like Voodoo, Umbanda, Quimbanda and SanterÃa, drawings are also used as talismans, such as with the veves of Voodoo; these religions also take into account the colour of the candles they light, because each colour features a different effect of attraction or repulsion.

Perfumes and essences (like incense, myrrh, etc.) also serve the purposes of attraction or repulsion. Popular legends often attributed magical powers to certain unusual objects, such as a baby’s caul or a rabbit’s foot; possession of these items allegedly endowed their magical abilities upon their owners.

Drawing of clay amulet unearthed near Tartaria, Romania

In Central Europe, people believed garlic kept vampires away, and so did a crucifix. The ancient Egyptians had many talisman for different occasions and needs, often with the figure of a god or the “ankh” (the key of eternal life); the figure of the scarab god Khepri became a common amulet too and has now gained renewed fame around the Western world.

A lead talisman, folded around the string with which it was worn, presumably around the wrist or ankle. Excavated in Karanis, Egypt, in a room whose contents date to the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D. It has never been unrolled, and its contents remain unknown.

For the ancient Scandinavians, Anglo-Saxons and Germans and currently for some Neopagan believers the rune Eoh (yew) protects against evil and witchcraft; a non-alphabetical rune representing Thor’s hammer still offers protection against thieves in some places.

Deriving from the ancient Celts, the clover, if it has four leaves, symbolises good luck (not the Irish shamrock, which symbolises the Christian Trinity). In the celtic tradition a bag made from a crane skin (called a crane bag) symbolised treasure, a wheel symboled the sun, a boat also was a sun symbol, but also a death symbol (to the land of the dead), the raven was a symbol of death, the head was a symbol of wisdom as was the acorn and a well.

Corals, horseshoes and lucky bamboo also allegedly make good talismans.

Figures of elephants allegedly attract good luck and money if one offers banknotes to them. In Arab countries a hand with an eye amid the palm and two thumbs (similar to a Hand of Fatima) serves as protection against evil.

Small bells in India and Tyrol make demons escape when they sound in the wind or when a door or window opens.

Buddhism has a deep and ancient talismanic tradition. In the earliest days of Buddhism, just after the Buddha’s death circa 485 B.C., talismans bearing the symbols of Buddhism were common. Symbols such as conch shells, the footprints of the Buddha, and others were commonly worn. After about the 2nd century B.C., Greeks began carving actual images of the Buddha. These were hungrily acquired by native Buddhists in India, and the tradition spread.

Another aspect of talismans connects with demonology and demonolatry; these systems consider an inverted cross (not an upward cross, which drives demons away) or pentagram in downward position as favourable to communicate with demons and to show friendship towards them.

The Christian Copts used tattoos as protective talismans, and the Tuareg still use them, as do the Haida Canadian aborigines, who wear the totem of their clan tattooed. Most Thai Buddhist laypeople are tattoed with sacred Buddhist images, and even monks are known to practice this form of spiritual protection. The only rule, as with Jewish talismans, is that such symbols may only be applied to the upper part of the body, between the bottom of the neck and the waistline.

During the tumultuous Plains Indians troubles in mid-19th century America, the Lakota Tribe adopted the Ghost Dance ritual, created by a Paiute Indian living in northwestern Oregon. Black Elk, the great Lakota Holy Man, received instructions on how to create a talismanic shirt that would protect the Lakota from the Greedy White Man’s bullets. Tragically, the shirts turned out to be just that: shirts.

Museums display many curious talismans, but one need not go far to see one, because they have never lost their influence on people of every nation and social status. We can see talismans in jewellery, fairs of artisans, shops, and, if we look carefully, even in our own homes, maybe on ourselves.

The need for talismans arose with the human race and the need of people for help and protection not only against supernatural powers but also against other persons.

War and other dangerous activities make the participants try to get the most luck they can. Carlist soldiers wore a medal of the Sacred Heart of Jesus with the inscription ¡Detente bala! (“Stop, bullet!”).

Š